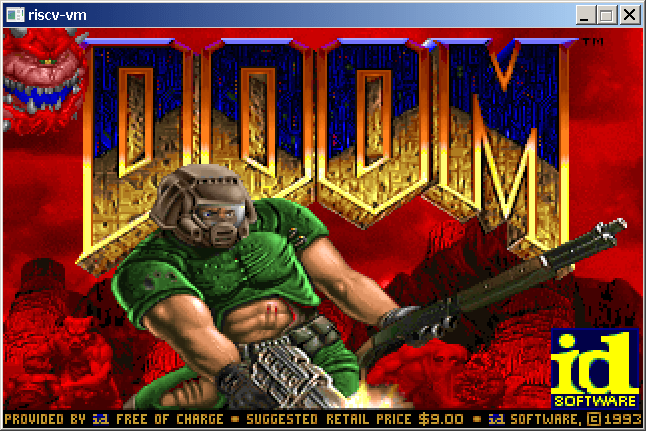

Recently I undertook a hobby project to recreate an IBM XT Personal Computer from the 1980s using a mix of authentic parts and modern technology. I had a clear goal in mind: I wanted to be able to play the EGA version of Monkey Island 1 on it, with no features missing. This means I need mouse support, hard drive with write access for saving the game, and Adlib audio, my preferred version of the game’s musical score.

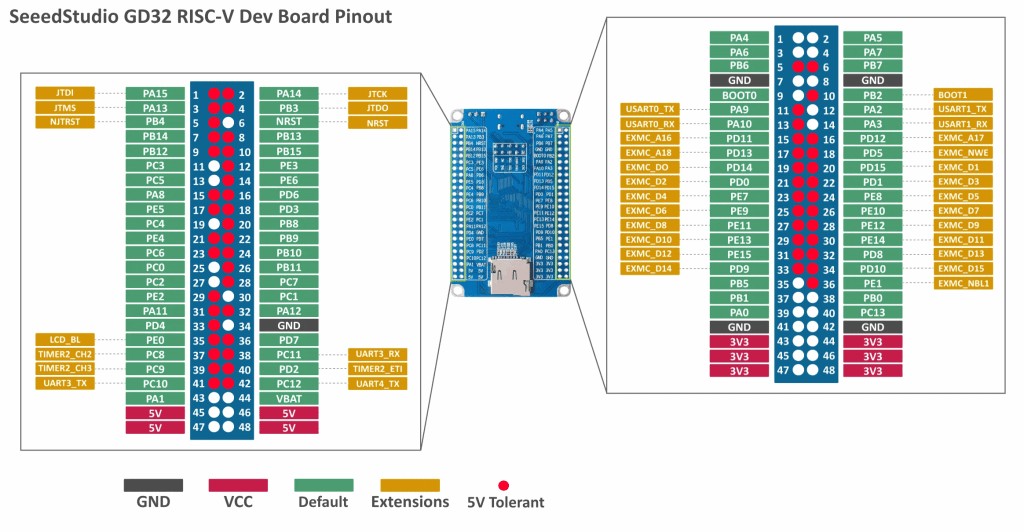

The catalyst for this project was the discovery that there are low-power versions of the NEC V20 CPU available (UPD70108H), which is compatible with the Intel 8088 used in the XT. Being a low-power version significantly simplifies its connection to an FPGA, which typically operate with 3.3-volt IO voltages. Coupled with a low-power 1MB SRAM chip (CY62158EV30) to provide the XT with its 640KB of memory, and I started to have the bones of a complete system worked out.

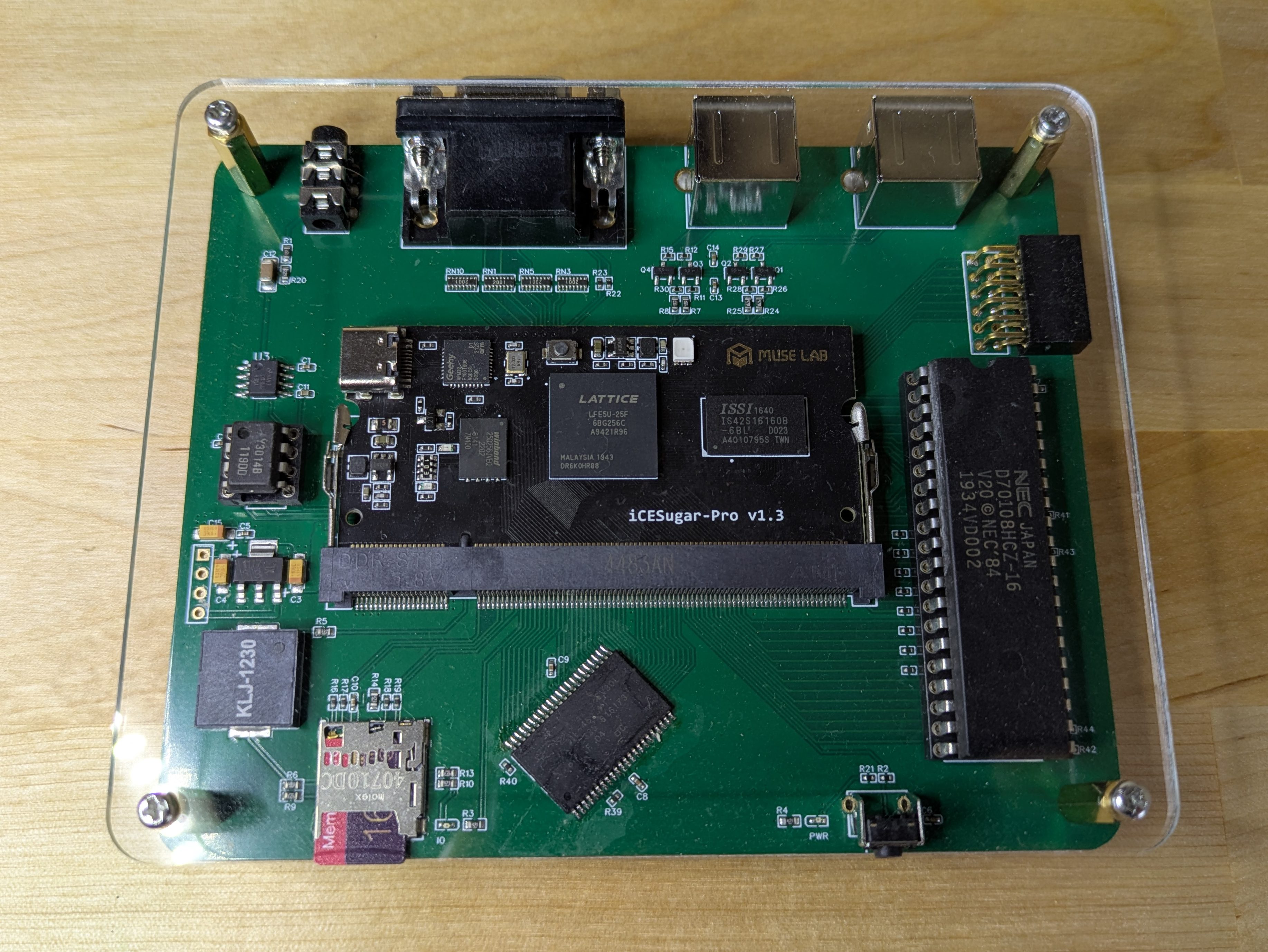

I started off by designing the hardware of the system, which would then serve as my development board while I worked on the software/gateware. The following features were added:

– DIP-40 socket for an low power NEC V20 CPU

– 1MB SRAM chip for the system memory

– An icesugar-pro FPGA board with a Lattice LFE5U-25F

– Dual PS/2 connectors for keyboard and mouse

– Micro SD card socket to act as a Fixed Disk

– An authentic YM3014B digital-to-analogue converter for audio

– A Piezo speaker that can be driven by the programmable-interval-timer for system bleeps

– Lastly, a reset switch and some status LEDs

I drew up my design using the EasyEDA CAD software as I’m already familiar with it, and it has really good integration with the JLCPCB PCB assembly service. Some of the components in the design are too tricky for me to hand solder by myself. I did however have to solder the SRAM chips once the boards arrived since they were not stocked by LCSC so I had to source them elsewhere.

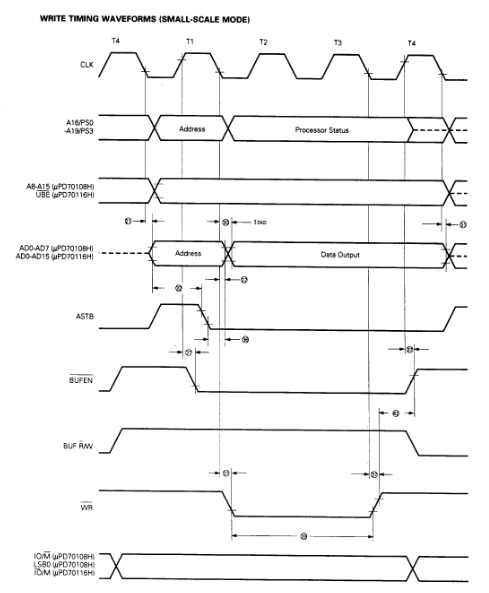

The first step was to write a bus controller for the processor. The V20 CPU clock is more forgiving than an original i8088 since its can be run right down to 0hz and its uses a regular 50% duty cycle. The external interface for an 8088 CPU operates in terms of bus cycles. At that start of a bus cycle the CPU asserts some pins to let everyone know what it wants to try and do… read memory, write to IO, etc. Each type of bus cycle follows a specific sequence of events that happen over a number of clock cycles. It was straight forward to make a state machine that could detect the start of a bus-cycle, figure out what kind it was, and then produce or consume the data as needed by the CPU. Key here, was to make sure that all of the timing requirements were met, so that signals the CPU generates are sampled at the correct time, and signals the CPU requires have been driven correctly before the CPU reads them.

My first test for the bus controller was to write a simple program using NASM to be executed on the V20, with a simple goal… it will flash an LED mapped to an IO port address. Simple, but a blinking LED seems to be the hardware equivalent of the software hello-world. For the initial version, the program was simply loaded into a FPGA block ram and used directly as the system memory.

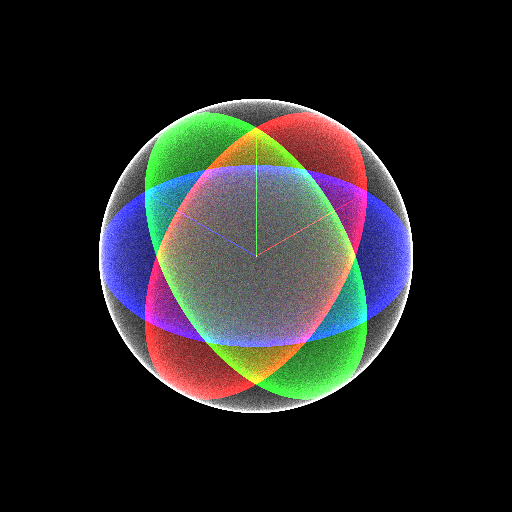

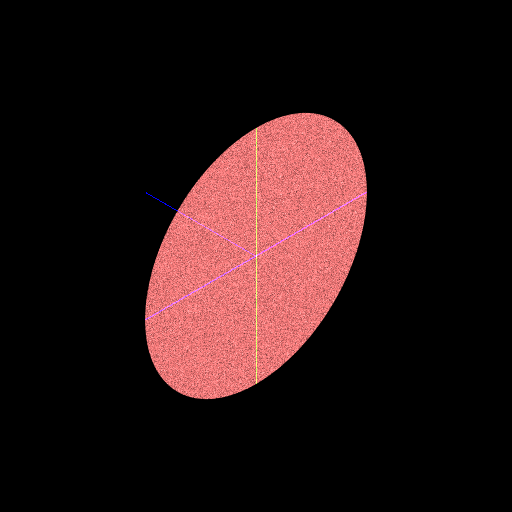

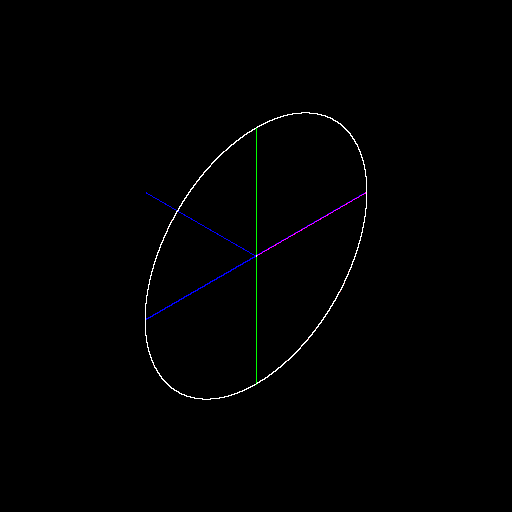

Later, I used a more complex approach for memory accesses. The bios, for example, is loaded into an FPGA block ram, so that CPU memory reads will come from that rather than the system SRAM chip. Video memory is implemented a differently still. CPU memory writes are passed to both the video memory block ram and system SRAM, but CPU reads alway come from only the system SRAM. This then means that I have a spare read port on the video block ram that can then be used by the VGA signal generator to display the video memory contents.

After my success with a blinky program, I installed a virtual copy of Supersoft/Landmark Diagnostic ROM in place of the BIOS and wrote a basic CGA adapter for video output. I was then able to use the diagnostic ROM to test the SRAM memory interface as well as some of the peripherals required by the XT such as the programmable-interval-timer (i8253) and programmable-interrupt-controller (i8259).

Once I was confident the basic system was stable I then swaped in a generic XT bios from https://www.phatcode.net in place of the diagnostic ROM. It was amazing to see the bios start to boot up, and complain when it couldnt find a boot disk.

Fixed Disk access is achieved by making a small Verilog SPI controller accessible to the CPU via some unused IO ports. I then wrote an option ROM to handle BIOS INT13H (disk service) calls, which had routines that could issue commands to the SD-Card over SPI. The tricky part for me was learning the SD card protocol and then writing 8088 assembly to perform the correct operations. The mapping itself is very straightforward as both SD card and DOS assume 512byte sectors.

I saved a lot of time when writing the option ROM by developing and debugging the code using a software emulator of the board that I cobbled together. Some historic sources for it can be found here: https://github.com/bit-hack/iceXt/tree/master/misc/emulator

Perhaps the hardest part of the project was, surprisingly, getting the mouse to work. Mice of the XT era would typically be connected to a UART serial port. I had however placed a PS/2 connector on the hardware board, and those mice use a very different protocol. In my efforts to support a mouse I startedto learn about PS/2 devices, however I would need to implement a much more complex keyboard controller, and the BIOS I was also lacked support for such modern peripherals, and I just plain didn’t feel like I understood everything required to get that working.

What makes it tricky is that PS/2 is a bidirectional protocol, and the mouse has to be asked by the PC to broadcast updates, otherwise we will not receive any. That added a lot more complexity than I was wanting. The keyboard on the otherhand is relatively easy to work with and send out keypresses without having to be asked.

I chose an alternative. I wrote some Verilog code to talk directly to the PS/2 mouse, which would early in the boot process tell it to start sending over mouse events, as they have to be requested. When the bridge then receives mouse events, it translates and presents them to the computer via a pseudo UART peripheral. I had implemented a basic PS/2 mouse to Serial mouse bridge. A little convoluted but it works really well.

During this process, I lobotomised a spare mouse by attaching a logic analyser the clk and dat pads inside the mouse. I was then able to capture the communications between a real PC and the mouse and observe it during use. This gave me invaluable insight into exactly how the protocol worked, and what a real mouse expected.

I also found that having real waveforms to look at made it much easier to test components of my design in verilator, a Verilog simulator, as I could closely model the stimulus it should see when running in the FPGA.

Just like the XT, one of the channels of the PIT timer is used to drive the internal speaker to produce bleep and bloop sounds. I extended this by having disk accesses trigger short pulses out of the peizo speaker as a crude emulation of a hard disk seeking. I think it really adds to the experience when you can hear your computer thinking away while doing its tasks. When it comes to music, the internal PC speaker quickly looses its charm however. Writing an YM3812 implementation (the FM chip used in the Adlib card) is beyond my skill level but thankfully Jose Tejada has written an amazing open source version that I was able to pull into my project; https://github.com/jotego/jtopl.

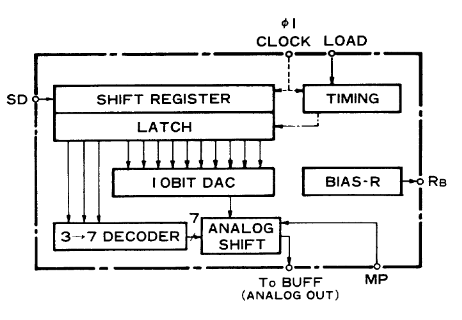

I wrote a small Verilog module to take the PCM sample data generated by this soft YM3812 and convert it to the unusual 3:10 floating point format required by the YM3014 DAC on my board. This is very similar to the operation of the real Adlib hardware, where the YM3812 generates and sends serial audio data to a YM3014 DAC chip. A modern I2S DAC may have been cleaner, but having a chance to play with the authentic DAC seemed a little more fun to me. All of this combined results in the same lovely crisp FM tones I was so fond of when I played games on my PC growing up.

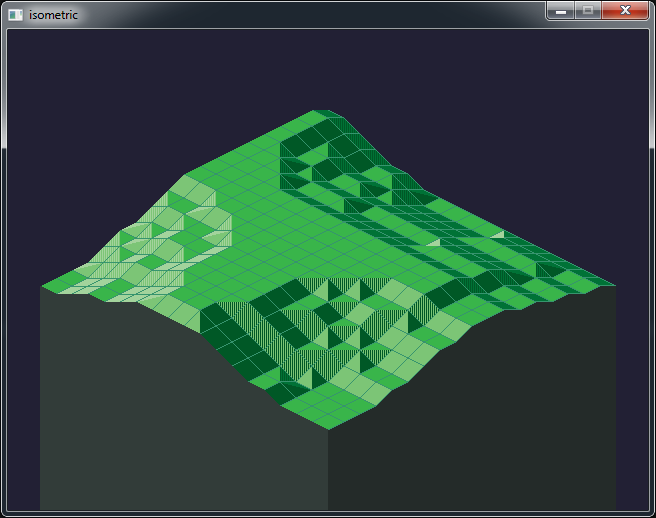

A lot of other elements of this project have been glossed over or omitted, such as support for CGA and EGA graphics. There is even a USB to UART bridge for sending files from a host PC directly to the SD card. I also made some nice clear acrylic panels on a CNC machine to round off the design and protect the bare PCB.

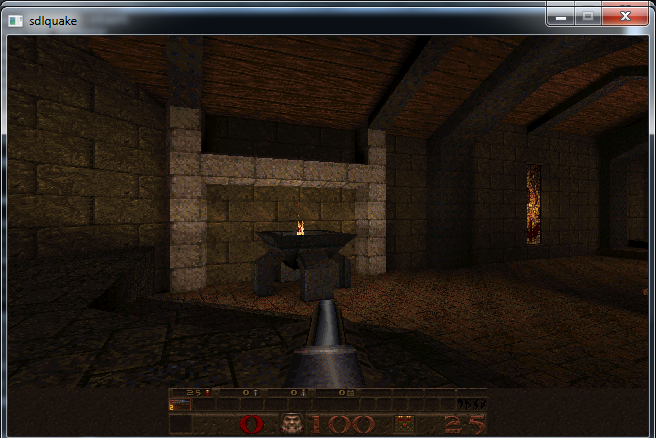

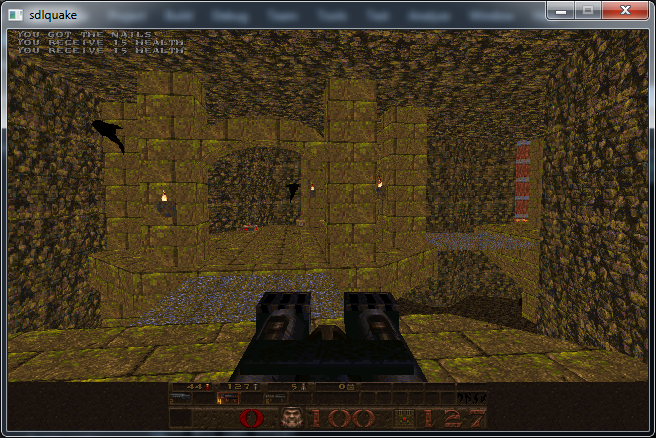

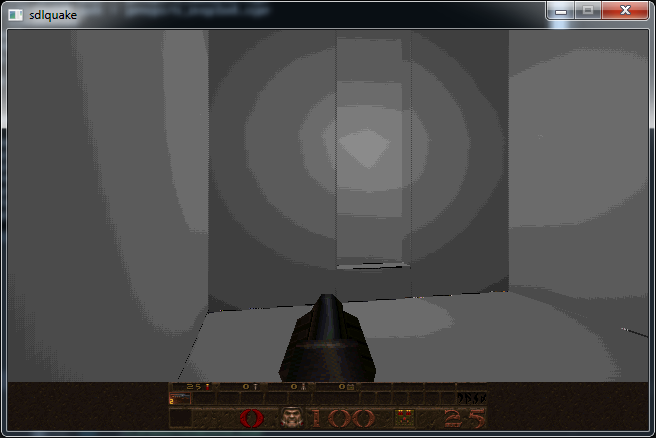

A video demo is shown below.

Unfortunately there is a ton of screen tearing due to the phase between the monitor and my camera. It isn’t visible in person.

Source code, schematics and gerber files are available on github here: https://github.com/bit-hack/iceXt

Thanks for reading!