I discovered in the final hours before submision of my Ludum Dare entry, Ninja Flare, the full horror of using a variable time step rather then a fixed time step scheme. What am I talking about? Well, the time interval between rendering two frames or between successive updates of the game world is entirely in the hands of the programmer. As the time between these events change, so the speed that the game plays will change. How do we ensure that the speed of the game appears and feels constant between different computers. To find a nice solution, lets explore this problem from the beginning and build up. The most basic inner loop of any program can be seen below:

while ( running )

{

clearScreen( );

updateGame( );

drawGame( );

flipToScreen( );

}

It is natural to follow this kind of program flow, but there is no consideration for the effects caused by the change in speed of the machine. The game will run at a speed determined entirely by how quickly it can execute this loop. This leads to the horrible situation where, the game might play beautifully on the programmers computer, but someone running it on a faster computer, aging hardware or a stressed computer will experience something very, very different. There are two common solutions to handle this problem. The first solution is to find a way to ensure that we only execute the updateGame() procedure, at set intervals of time, and not faster or slower then this. The second method is to scale all of the movements in our game so that they happen in proportion to real world time. The first method is called a fixed time step scheme, and the second is referred to as a variable time step or delta time scheme. Lets have a look at some of the advantages and disadvantages of each method.

A fixed time step scheme is by far the simplest method to program, as we will see shortly. All of the logic of the game can be hard codded, safe in the knowledge that the game will update at the same rate, all the time. When using Newtonian physics in a game, as is so common, many of the methods for integration used to advance the movement of objects, are extremely sensitive to changes in time step. This is because, the smaller the time step for these integrations that is used, the better the accuracy of the simulation will be. If we have even just one frame with a large time-step, then large errors can instantly ruin the movements of your objects. A common symptom of this kind of error is objects that fly through walls or just objects that seem to vanish instantly, being a situation called simulation blow up. An example is shown below:

// start off with the current time

float oldTime = getTicks( );

while ( running )

{

// find the time scale

float newTime = getTicks( );

float scale = (newTime - oldTime) / 1000.0f;

oldTime = newTime;

clearScreen ( );

updateGame ( scale );

drawGame ( );

flipToScreen( );

}

This may look simple but there are many devils lurking in the details. This computes a variable ‘scale’ that provides a floating point scale between updates relative to a one second period. The faster the loop updates the smaller this value becomes, thus scaling all movements by this value should in theory lead to the appearance of a constant movement speed regardless of the execution speed. This leads to the horrible situation where ‘* scale’ will show up in every line of code, reducing readability, which is something that should not be underestimated. Also it becomes tricky to integrate this with Newtonian physics, when applying forces, impulses and the like, regardless of the blow up situation described earlier. Some major advantages to using a variable time step however is that the game will appear to look and feel smoother on a faster computer as well as putting every execution of the main loop to good use, since we are always advancing the game state. There are many articles online, covering the advantages and disadvantages of this technique, as well as ways to make it more robust. There are methods to minimize explosions, through filtering the scale time, over a few frames, or limiting the range of this variable all together, all of which I have tried myself. I have had my fingers burned with this technique however so I want to explore the fixed time step approach for my game.

A very naive implementation of a fixed time step approach is shown below:

//

int time = getTicks( );

const int interval = 16;

while ( running )

{

while( true )

{

// find time since last intervall

int dt = getTicks( ) - time;

// have we waited long enough

if ( dt >= interval )

{

// advance one interval

time += interval;

// exit the stall loop

break;

}

}

clearScreen ( );

updateGame ( );

drawGame ( );

flipToScreen( );

}

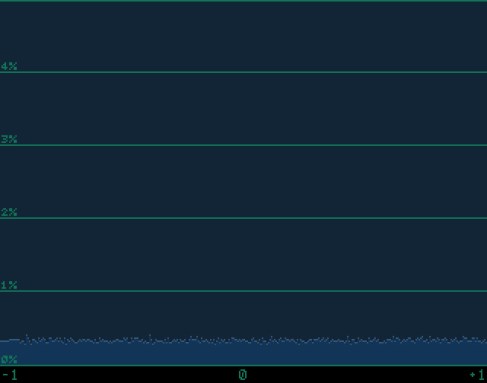

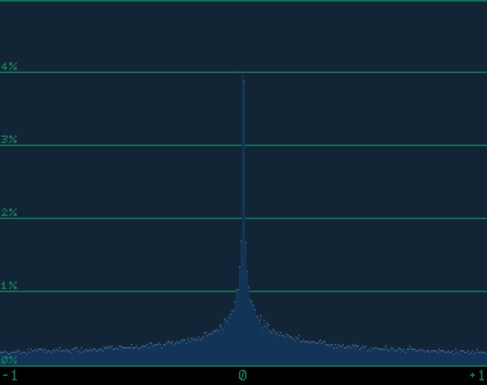

It may look complex but in reality the concept of a fixed time updater is very simple; we simply sit in a useless while loop until it is time to process the next frame. It is extremely wasteful of a computers resources, since we literally do nothing for long periods of time, just wasting CPU cycles. Worse still, the operating system has no way of knowing that we are just wasting time, so it cant do anything useful with this time. If you look at the CPU usage for an application using such a strategy, you will see it is extremely high, independent of the complexity of the game itself. This is in fact worse then the variable time step method shown above, since at least then cycles can be given back to the operating system while waiting for vertical blanking period in the ‘flipToScreen()’ function. Let me present another version that will try to make this fixed time step a little more efficient in this respect.

//

int sleepThr = 6;

int time = getTicks( );

const int interval = 16;

//

while ( running )

{

clearScreen ( );

while( true )

{

// we can do things that are not effected by execution speed

processWindowMessages( );

// find time since last intervall

int dt = getTicks( ) - time;

// if we are too fast then give cycles back to the OS

if ( dt < sleepThr )

sleep( 1 );

// have we waited long enough

if ( dt >= interval )

{

// advance one interval

time += interval;

// exit the stall loop

break;

}

}

updateGame ( );

drawGame ( );

flipToScreen( );

}

The situation with this fixed time step scheme is a little more forgiving then the previous one. I included a method to give cycles back to the operating system, when we can be sure that they wont be needed. This is done through call to the ‘sleep()’ function, which in reality can be ‘SDL_Delay(1)’ if using the SDL library. It is important to realize that any call to a sleep function cannot be guaranteed to only last for the time that was specified, since there are many factors the OS has to deal with that could delay control being given back to our application. That is why I ask to delay only for one millisecond, since this can in fact last up to somewhere around 10 milliseconds in practice, although it could potentially be much higher. We can also do many useful housekeeping tasks with our cycles that are just sitting waiting to be burned, for instance, that is an perfect place to process window messages. We could even update any game scripts during this time, later updating any that still need to be executed during the actual ‘upadateGame()’ call. Also by placing the clear screen call before the burn loop, we can come much closer to presenting the next frame to the screen as soon as possible.

One problem still persists however, and exists in the variable time step code too for that matter. If we were to debug any of these applications, then as we step out of the debugger to continue the program, we would see the game played in fast forward for a time proportional to that spent in the debugger. Why does this problem occur? It happens because while we debug the program, our difference in time since the last frame was processed grows massively. The game then falls through the burn loop until it has processed enough frames to catch up with the current time. This is a big problem, essentially ruining the game upon stepping out of the debugger. We could fix this by changing a single line of code, but I do not recommend this method:

// have we waited long enough

if ( dt >= interval )

{

// bad way to advance one interval an avoid debug problem

time += dt;

// exit the stall loop

break;

}

This method can introduce errors since we now present a new frame “no quicker then our interval time”, but it could be longer, since errors that slow us down wont be corrected for. This gives us a situation where the game could jump and stutter, giving us a slowing effect. We can do much better then this by introducing a hard limit to the time between updates, by adding the following code:

//

int sleepThr = 6;

int time = getTicks( );

const int interval = 16;

const int blowThr = 32;

//

while ( running )

{

clearScreen ( );

while( true )

{

// we can do things that are not effected by execution speed

processWindowMessages( );

// find time since last intervall

int dt = getTicks( ) - time;

// account for condition where the timer just wrapped around

if ( dt < 0 )

{

time = getTicks( );

continue;

}

// if we are too fast then give cycles back to the OS

if ( dt < sleepThr )

sleep( 1 );

// limit our max lag time

if ( dt > blowThr )

// just come right up to current time

time += dt;

// have we waited long enough

if ( dt >= interval )

{

// advance one interval

time += interval;

// exit the stall loop

break;

}

}

updateGame ( );

drawGame ( );

flipToScreen( );

}

The time step routine is thus much more robust now to situations where the time to process a frame is far greater then we anticipate for. It recovers from this situation, by simply resetting the time stepper, and proceeding as normal. We have thus created a nice situation where the game may not proceed any faster then a given time and if it advances a little slower, then it has a chance to catch up. If it proceeds far slower however then the game just proceeds regardless and attempts to time step again after this worst case. I also added code to account for one small error condition that has so far not been mentioned. If the tick timer gets too large, it has the potential to wrap around, thus causing a situation where, dt, would become negative, where upon it is obvious to see that it would meet the “dt < sleepThr” condition and appear to permanently sleep. We can easily reset the time stepper if dt were to ever go negative, and at worst get a frame long stall.

This is the current time stepper that I will use as part of my game. As far as I can see it should perform quite nicely, but the proof is in the pudding as they say, so lets just hope it stands up as well as the theory seems to when it is put into use.